Chapters

Preliminary 2. Bibliographical Alterities

As already discussed, in his 1996 groundbreaking book, The Darker Side of the Renaissance, Walter Mignolo posed a clear critique of the standard account of writing systems. This commonly accepted version of this history was derived from such well-respected early 20th-century scholars as Ignace Gelb and David Diringer. In their account, writing systems “developed” through a series of “progressive” stages from “proto-writing” in pictures and signs to an advanced “true” alphabetic script, taken to be the highest level of achievement in this technological matrix. We should keep in mind the extent to which Diringer and Gelb, among others in the early and mid-20th century, were still piecing together the archaeological evidence on which such a master narrative could be constructed. Well into the 19th century, cleric-scholars like the British Charles Forster and others were still tracking the “one primeval” language and script or attributing the invention of writing to a divine origin. So the “modern” formulation of progress has to be seen in its own historical place. But, as Mignolo points out, the typology of the Diringer/Gelb approach (still largely used in current studies of the history of writing and the alphabet), enforced a binaristic hierarchy in which the writing systems of the New World, in particular, were subject to a prejudicial assessment and characterized as inferior, inadequate, or undeveloped.

The larger point Mignolo makes is not just that these materials cannot be fitted into a standard model of bibliography, but that we might rethink the foundations of our approach to writing, literacy, books as a result of a fresh encounter with these materials and their conditions of production and use. In essence, Mignolo is launching an attack on the fundamental coloniality of knowledge in the realm of bibliographical studies and suggesting that it be rethought.

If we take this seriously, the challenge we face is to think about what a future history of the book would look like if it began its formulation with the inclusion of New World examples of writing. Rather than present indigenous glyphs, signs, quipu, and wampum as anomalies or exceptions to a “normative” bibliography, they would form part of the field of practices and works on which bibliographical studies would be constructed. Similar sentiments and impulses can be found in the small but growing literature that scholar Jesse Erickson designates with the term “ethno-bibliography”.1 Robert Fraser, Birgit Rasmussen, Betty Booth Donahue, D.F. McKenzie and Phillip Round, Matt Cohen, as well as Mignolo provide crucial references for beginning to develop this changed concept of “the book” and putting it into constructive dialogue with the prevailing/current models of book history.2

In his work on encounters between old and new world cultures, Jared Diamond makes the point that “guns, germs, and steel” and “alpha-numeric notation” were not “superior technologies” to those found among the indigenous people, but they were embedded in a technological system. This allowed “instrumentalization of control” in a way that shifted and skewed power relations from the outset.3 In other words, a techno-ecology, not technology, is what we have to examine if we are to understand the contact encounters—and more important, learn from them. The imprint of the “technology” model—the core of which is what Mignolo is pointing to in his analysis of the “progressive” version of writing systems “advancing” towards the alphabetic—is still so present and prevalent that we barely see it. The naturalization of colonial power in knowledge production successfully conceals its workings. How to undo this?

For works outside the western tradition (or even within it) the object constituted by the historical and theoretical inquiry may be an event space. There may not be an object, only a distributed condition of literacy and/or semiotic communication across physical traces and inscriptional or productive apparatus. Rather than relying on a forensic, descriptive, object-based approach for analysis, such an object may have to be conceived from a performative approach. Even where actual books are part of this alternative legacy, they call for reading of the polysemous field of their composition and conception and their performative dimensions, rather than by assuming their literal, physical, or textual self-identity. The cultural parallax described in D.F. McKenzie’s still dazzling study of the “Treaty of Waitangi” has to be expanded beyond the discussion of two crossed gazes, each from a different cultural perspective.4 McKenzie carefully exposes the misunderstanding the colonial and aboriginal had about each other’s assumptions with regard to the symbolic and literal value of an object, a still-binding treaty.5 Using this example, he creates an analytic model in which attention to constitutive processes replaces the assumption of an a priori object that is misread—the “treaty” is not the same thing within the views of different cultural perspectives. Marking, making, inscribing, reading, are all aspects of a system of social and cultural production. A semiotic object does not sit inside it, like a gem in a setting, in a context-based model of object and conditions. Instead, the object is constituted, like an organism in a medium, as an effect of the very conditions that bring it into being. In the same way that cell walls and chemical/physical/biological processes create the conditions of semi-autonomy that define a living organism in an ecological system, the semiotic “object” is an effect of constitutive conditions in the culture of which it is an integral part.

What does this mean for books? Bibliographical studies? As long as difference is construed as otherness, the asymmetry of these colonializing discourse persists. How, then, do we move beyond this? A few concrete examples in scholarship of the last two decades may show the way.

Elizabeth Hill Boone, whose volume, Writing Without Words (co-edited with Mignolo), was published in 1994, also 20 years ago, was already aware that she was working after two decades in which post-structuralism and deconstruction had shaken up the authority of text and power relations. Jacques Derrida’s reformulation of the primacy of “writing” over the authority of “voice” was, however, remote from the literacy studies formulated by Jack Goody, Walter Ong, and the Canadian media theorists around Marshall McLuhan. Theoretical ambitions had a difficult time getting traction on material realities. Bibliography remained book-based, antiquarian in its attention to the physical facts of collation, misprint, wrong-font and crooked sheets with overprints and recycled dingbats, cuts, or initial letters. A study of variant forms of reproduction as a way into recovery of the bibliographical narratives of print artefacts, met critical textual studies only in the work of a few scholars.6 D.F. McKenzie’s interest in the sociology of texts took studies of power relations into concrete realms of historical archive and event, and it is these figures whose notions of a performative concept of the book, with its emphasis on the codependence of conditions of production and circumstances of use, provides a foundation here. From these, as well as the other strains of intellectual thought already mentioned, we can begin to see both the limits of traditional bibliographical models for an encounter with “alterity” and to sketch an approach that is not “post-colonial”—i.e. a task of corrective recovery and retrospective inclusion of new examples to an old paradigm—but “de-colonizing,” to use Mignolo’s term, a project of rethinking the fundamental frameworks that constitute the object of inquiry at the center of our field. On what foundations, then, do we conceive of the “book” that comes to figure on such grounds? What, in fact, is a “book” in this shifted frame?

In the contact zones of the 16th and 17th centuries the assumptions underpinning western bibliography are exposed and their limitations revealed. The literal, forensic, formal materialities on which it operates have to be extended by a performative materiality. This means thinking about bibliographical objects in terms of what they do, how they work, not just what they are. Taking this one step farther, a constitutive performativity asserts that an object emerges from the co-dependent conditions in which it appears. More on this in a moment, first, some examples.

In her study of William Bradford’s 17th-century text, Of Plimoth Plantation, Betty Booth Donahue shows the extent to which his document, so often read as a colonial account of “discovery”, is also a record of the “indianization” of the colonists.7 To cite Donahue, “In American Indian epistemology the earth is First Text, and the study of its features constitutes textual exegesis.” Within the frameworks of this alternative semiology, Donahue tracks Bradford’s absorption of spatial constructs and directions, cosmology, and knowledge of natural history as they are encoded in Indian systems of language, work, and ceremony. Bradford absorbed the structuring principles of native cosmologies into the language in the text. The work is constituted as a border zone which embodies the native tribal leaders’ realization that they were “preparing the land for a new narrative”.8 The outcome was not inevitable at the outset, and though its course is marked by fatal asymmetries, this re-reading and rethinking allow an alternate bibliography to take root as one aspect of a de-colonization of current epistemology.

Phillip Round opens his book on printing in “Indian Country,” Removable Type (2010), with a study of the volume commonly known as the “John Eliot Bible.”9 He says, “In their stubborn materiality and monumental presentation, however, books were […] useful signs of the “visible civility” Eliot demanded from his Native parishioners.”10 He goes on to paraphrase the work of Matthew Brown, a scholar whose work emphasizes the ways “the culture of the book in Puritan New England provides us with ample opportunities to explore Euro-American settlers’ representations of imagined Native peoples,” and all the asymmetries that implies. But, as Round goes on to say, Brown, like many scholars, refuses to view “the books in the Indian Library as ‘ethnographic facts drawn from the contact zone or as neutral sources of Algonkian expression.’”11 Round asserts, instead, that the Indian Library “actually grew out of a fundamentally unstable bicultural communicative field.” Round takes apart each step of the composition of the Indian Bible, demonstrating that its translation, orthography, composition, and design function as a “crucial mediating semiotic in New England’s colonial middle ground”. Eliot was dependent on collaboration with Christian Indians “to work up a syllabic orthography of the Massachusett language.” James Printer, the “Nipmuck convert,” and Job Nesuton worked closely with Eliot to produce the Bible. I’ll cite again: “The physical properties of the 1663 Mamusse wunneetupanatamwe up biblum God […] reveal the collaborative, bicultural social horizon from which the Native print vernacular emerged.”12 Round goes on to note all of the details in layout, typography, and design that differentiate the Algonquian Bible from the English one; stressing the impossibility of translation, “the Algonquian vernacular cannot stretch to accommodate many of the underlying ideological principles of either Protestant doctrine or book culture that inform the Bible’s production.”13 And, “In the Algonquian edition, the concept of ‘book’ itself is untranslatable.” Thus the pages are peppered with a kind of hybrid Algonquin-ish, with “words ‘Booke,’ ‘Bibleut,’ ‘Chaptersash,’ ‘Bookut,’ and ‘Bookash’.”14[Figure 1]

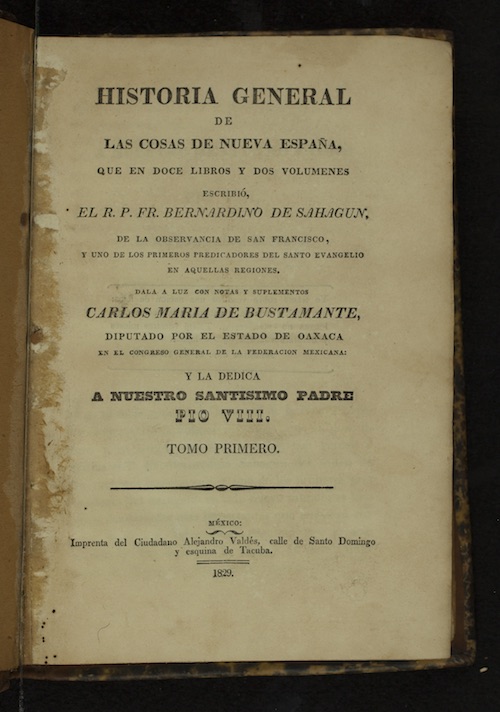

Contact encounters erased the literacies and practices of indigenous people. We know this, but revisiting the way these encounters have been written and assessed forces a reconceptualization of bibliographical studies. This is only being demonstrated in more recent work. In Queequeg’s Coffin (2012), Birgit Rasmussen recounts debates about relations between knowledge, recording practices, and sign systems in the literate cultures that existed in the New World at the time of contact.15 Her argument focuses on ways that the concept of “literacy” is a colonizing discourse that has to be dismantled and rebuilt if the full inventory of non-western notational frameworks are to factor into it. Among other indigenous forms of literacy, for instance, she discusses the practices by Indian warriors of putting public postings along their routes, in waterproof ink, as a distributed information system across the landscape. Native languages included terms for writing and grammar. Wampum was its own system of encoded information, never meant to be separated from the context in which it was used, and served as the foundation of oral recitation and performance. Such artifacts have to be approached through a revised bibliographical mode, not as static objects under examination, but as transactional objects whose very identity is constituted through exchange. The erasure of these practices has been systematic, as she demonstrates over and over again, through citing the repeated assertion that native peoples lacked writing—or lacked “real” writing. The painful history of the Mayan and Aztec codices is too familiar to need repetition (it is described in Chapter 6), but rethinking the still extant and remarkable documents produced by Bernardino de Sahagún, with his native scribes, along with that of Guaman Poma and his Nueva corónica and buen gubierno”, the Popul Vuh narratives of the Guatemalan highlands, the Chilam Balam (Mayan works from the 17th and 18th centuries) as an “inter-animated” semiotic exchange, she offers a way to think through a “decolonizing” scholarship in and through bibliographic practice.

Contact zones characterize 16th- and 17th-century encounters between the old world of the European “West” and the New World cultures (whose established communication and semiotic systems were so radically different from those of the colonizers that they disturbed their epistemological belief systems–and thus distorted, rejected, ignored, or attempted to eradicate the evidence of their existence). These exchanges, so important to the philosophical formulations of the late Renaissance and early Enlightenment, where the questions about peoples, identities, universal history, language, religion, civilization, and humanity all came up for question, are particularly useful as the starting point for thinking about bibliographical work now and for the future. (Mignolo is one of the entry points into this literature.) Why? Because the systems-ecological approach to the semiotics of biblio-literacy exposed in those encounters has implications that have been engaged only somewhat in the field of book history and bibliography to date.

As we face the pedagogical challenge of formulating future histories of the book, we have to move beyond connoisseurship and antiquarianism, into this realm of meta-bibliographical description. We need to defamiliarize our own practices of forensic attention to production histories and reception histories and attend to the assumptions on which they work. Can we learn to conceive of books differently by shifting our frameworks from western-based conceptions of bibliography to ones grounded in an ethnographic alterity?

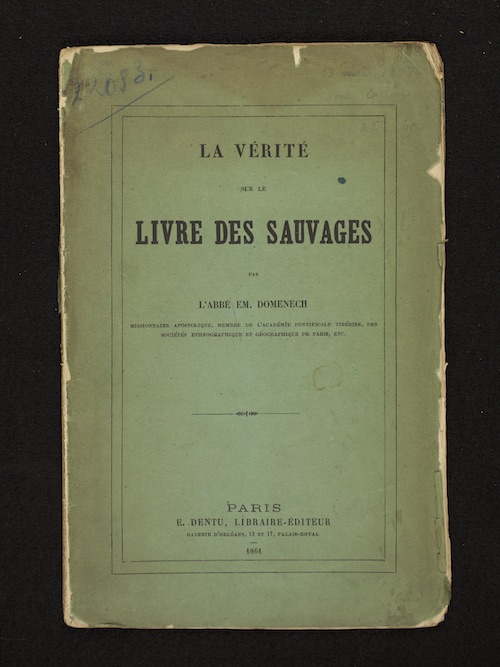

The approaches to this question informed by the study of books, literacy, writing, and inscriptional forms of knowledge and communication are not aligned with traditions of bibliographical study. The future of book history should be altered radically by including these works in a bibliographical approach that included these diverse forms, rather than positioning them as “other” to its “mainstream” traditions. Such a shift might have wider implications for ways diversity is understood within intellectual and historical frameworks. We might change our conception of “books” from an idea that they are “objects of knowledge” to the notion that they are elements of “knowledge ecologies” that exist in a co-dependent relation to the cultural systems of production/reception in which they function. The point is not merely to extend bibliographical or historical frameworks to include previously little studied or marginalized works, but to reconsider the foundations on which such frameworks established their own “colonizing” approaches to bibliographical knowledge, and to undo them in a way that takes up the call for “de-colonization” in other intellectual realms.[Figure 2]

How might we take these principles into analysis in such a way that they turn back onto our engagement with familiar objects, the books and documents of our own environment? If we are to effectively decolonize, then we cannot continue the process of dividing the world of cultures into “their” and “our” practices. What if we were to approach any familiar book and try to sketch the bibliographical approach that would situate it within the parameters of a biblio-alterity? Or grapple with text messaging, signage in the landscape, the integration of virtual and analogue signals and the multimodal interactions on our many screens and devices? Traditional bibliography can accommodate only a fragment of these—it can hardly deal with the iterative versioning of texts in a digital format—and yet, they are all aspects of current literacy technologies and cultural practices. Unless we engage the objects of traditional bibliographical study with the decolonizing methods that have emerged from the study of non-western materials, we will continue to divide the world into “their” and “our” objects and approaches, which would simply continue the process of othering that is at the heart of colonial epistemologies.

Notes

1 Jesse Erickson, a former doctoral student in Information Studies at UCLA first introduced me to this term as part of dissertation research; he borrowed it from Hugh Amory. ↩

2 Robert Fraser, The Book Through Postcolonial Eyes (NY and London: Routledge, 2008), Birgit Rasmussen, Queequeg’s Coffin, (Chapel Hill, NC: Duke University Press, 2012,), Betty Booth Donohue, Bradford’s Indian Book (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011) D.F. McKenzie, Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts, (London: British Library, 1986) Phillip Round, Removable Type (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), Matt Cohen, Networked Wilderness, (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), and the recent volume co-edited with Jeffrey Glover, Colonial Mediascapes, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014) ↩

3 Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel (NY: W.W. Norton, 1987). ↩

4 McKenzie, op.cit.↩

5 Debates about the treaty, which is actually a series of nine documents, not a single artifact, continue into the present. ↩

6 See Jerome McGann, Radiant Textuality (London: Palgrave, 2001). ↩

7 Donohue, op.cit. ↩

8 Donahue, op.cit. ↩

9 Round, op.cit. ↩

10 Round, op.cit. ↩

11 Round, p. 25 ↩

12 Round, and earlier, op.cit. p. 26 ↩

13 Round, op.cit. ↩

14 Round, p. 29. ↩

15 Rasmussen, op.cit. ↩

Figure 1.

Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de Las Cosas de Nueva España.

Figure 1 Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de Las Cosas de Nueva España, Mexico, 1829.

F1219.S13h 1829

Sahagún’s monumental study of the customs and manners of the Aztecs was written over a forty year period, between 1540 and 1585, and based on direct observation as well as engagement with native peoples in New Spain. He had assistance from native artists, whom he trained to use pen, ink, and watercolor to make many of the images and studies. The hybrid of western and native motifs and graphical styles is evident and shows how much observation is already encoded with cultural perspectives.

↩

Figure 2.

L’Abbé Emmanuel Domenech, La Vérité sur la Livre Des Sauvages. Paris E. Dentu, 1864.

E98.P6 D7

This study focused on what was proved to be a fake manuscript, actually composed by a German writer in the 18th century, but taken by Domenech as a genuine work by Native Americans. Domenech’s misreading offers insights into clichés and assumptions about how Europeans viewed American Indians through a gaze of Western literacy standards. Domenech's projections of his own expectations repeat acts of intellectual colonization from earlier periods.

↩

All images are from book in the Charles E. Young Research Library at UCLA, unless otherwise noted.