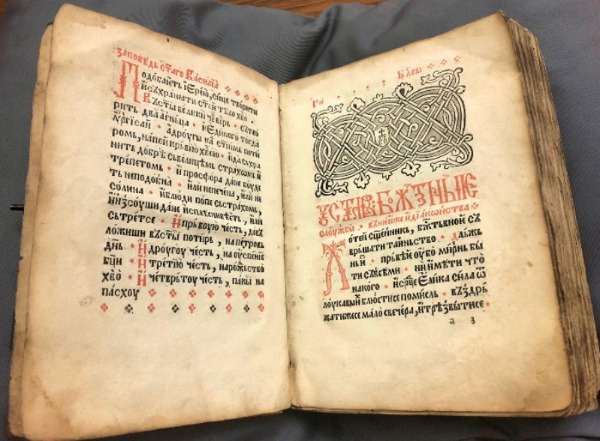

Sluzhebnik, ustav Bozhestvenniyia sluzhby, Orthodox Eastern Church, Venice, 1554. Z233.I8 O78h 1554. This beautiful example of Serbian Church Slavonic printing incorporates large ornamental red initials, intricately knotted head-pieces, and subtle diamond patterns to create lovely flowing pages. Although this liturgical text would be used in the service of Eastern Orthodox worship the Old Cyrillic type has a storybook quality to it that brings to mind Slavic folklore and fairytales.

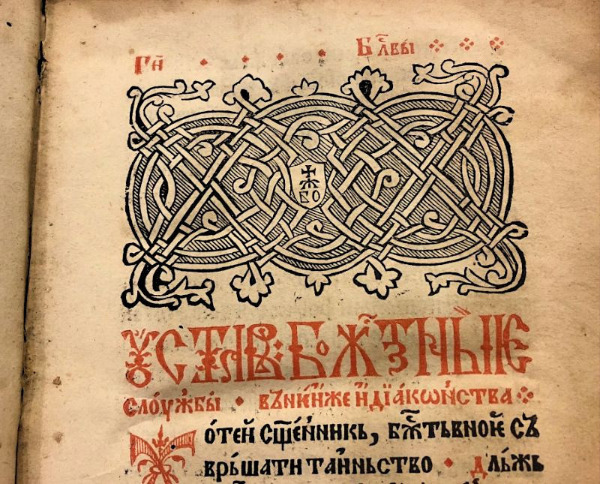

Sluzhebnik, ustav Bozhestvenniyia sluzhby, Orthodox Eastern Church, Venice, 1554. Z233.I8 O78h 1554. In the center of this head-piece Bozidar Vuković’s printers mark Б О is visible. Vuković’s headpieces were influential in Slavic printing and were known throughout the Slavic world (Wikipedia 2018).

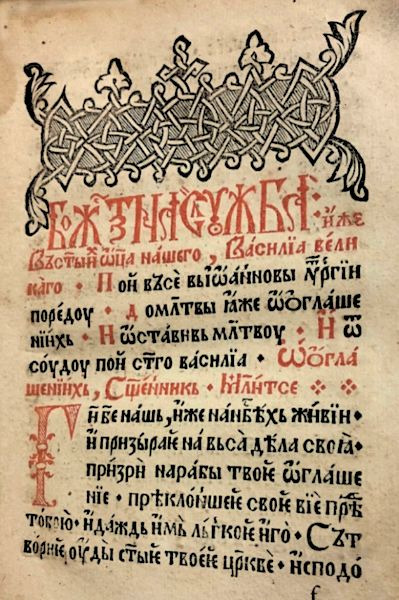

Sluzhebnik, ustav Bozhestvenniyia sluzhby, Orthodox Eastern Church, Venice, 1554. Z233.I8 O78h 1554. This is the second decorative head-piece in this Sluzhebnik. It is slightly different in style from the example above. Although it is smaller and lacks Vuković's printers mark, it is by no means less beautiful or influential.

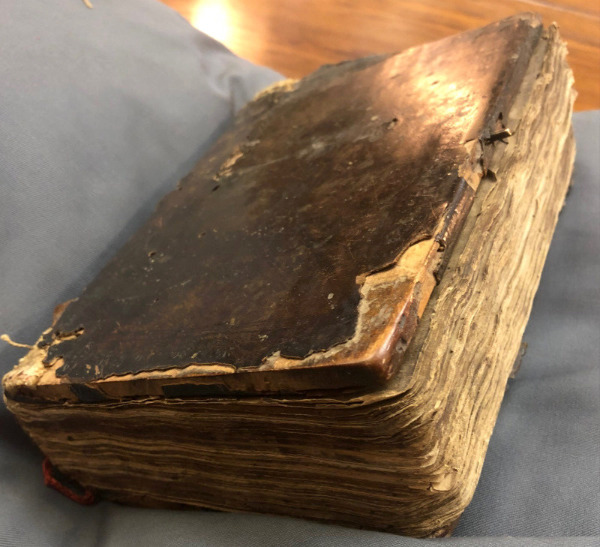

Sluzhebnik, ustav Bozhestvenniyia sluzhby, Orthodox Eastern Church, Venice, 1554. Z233.I8 O78h 1554. This Sluzhebnik was sturdily bound in a Coptic binding in order to withstand a high volume of use. As a liturgical text it would have been consulted whenever an Eastern Orthodox priest conducted services. The covers, although showing signs of visible wear, have held up well over the centuries. The stitching is still intact and the mechanics of the book function as intended.

Sluzhebnik, ustav Bozhestvenniyia sluzhby, Orthodox Eastern Church, 1554

This work, from the mid-16th century, is an example of Church Slavonic printing executed by the Vuković printing house established in Venice in 1519 (Wikipedia 2018). Sluzhebnik, or the “book of priests,” is a liturgical text used in the practice of the Eastern Orthodox faith (OrthodoxWiki 2012). This Sluzhebnik is a portable, easily handleable object, and has a sturdy coptic binding with covers of wood board wrapped in leather. It is printed in red and black ink with large ornamental red initials and intricate woodcut head-pieces. The first head-piece contains the symbols Б О inside interlocking knotwork. This is the printers mark used by Bozidar Vuković, the founder of the Vukovic printing house. This copy of Sluzhebnik is a reprinting of the original 1519 edition executed by Božidar’s son Vićenco Vuković (Wikipedia 2018). Via this beautiful and unassuming religious text we can access the complex history of the development of Slavic literacy and the role Church Slavonic played in its development.

The Slavic languages all likely stem from one “Proto-Slavic” root in use about two thousand years ago in what is now modern day Ukraine (Press 2008, 7; Nesset 2015, 5-20). As the population of the region spread further apart the languages and cultures diverged (Nesset 2015, 5-20). By the 9th century CE the West Slavic (Czech, Slovak, Polish), South Slavic (Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbian, Croatian) and East Slavic (Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian) languages had developed into substantially different forms from one another, but none had yet to develop a writing system. The Slavic writing system came in the middle of the 9th century CE as a deliberate response to the encroaching threat of Catholicism and Latin via the Carolingian Empire (Nesset 2015, 33-36).

In 863 CE two brothers, Constantine (St. Cyril, posthumously) and Methodius, were dispatched to Moravia (modern day Czech Republic) from Byzantium at the bequest of the Moravian Duke Rostislav to help teach the Gospel in Slavic. In order to provide access to holy texts in Slavic, Constantine devised a writing system for the Slavs. This writing system, known as Glagolitic, was based primarily on the Greek alphabet with new letter forms invented for unique Slavic sounds. Glagolitic codified a hieratic language that became known as Old Church Slavonic (Press 2008, 7; Bennet 2011, 6). Glagolitic developed further under the followers of Constantine and Methodius to become the Cyrillic alphabet in honor of its creator, St Cyrill (Nesset 2015, 33-36). Old Church Slavonic morphed into Church Slavonic and with the Christianization of the Slavs, around 980 CE, the language and writing system spread throughout the entire Slavic world.

It is important to understand that Church Slavonic was never a spoken language. Hieratic languages are defined by Bennet, via Wexler, as “unspoken languages of liturgy and culture” (Bennet 2011, 12). Like the medieval use of Latin in the Catholic Church, Slavonic is a language of ritual connected to the Eastern Orthodox faith. However, it is important to distinguish Church Slavonic from Latin in several ways. Latin was the spoken and written language of antiquity and birthed the Romance languages. It has a long history outside of the Catholic Church. Church Slavonic shares a common root with all Slavic languages and influenced their development, but it is inaccurate to say that Slavic languages stem from Church Slavonic. The Slavic languages and Church Slavonic have a parallel history and were used in very different contexts, the former for everyday communication and the latter for ritual and spiritual purposes (Bennet 2011, 6-13). It is interesting to note that the Church Slavonic of Božidar and Vićenco Vuković’s Sluzhebnik, which is an example of Serbian Church Slavonic printing, would be very similar to texts printed in Russian Church Slavonic of the same period, but neither are interchangeable with the Serbian or Russian languages.

For all of its influence on the Slavic languages, Church Slavonic has experienced periods of repression. Under the Islamic Ottoman empire, which ruled over South Slavic Serbia from the mid 16th century to the early 19th century, Eastern Orthodox worship and Church Slavonic printing was prohibited (Ivic 1995). The Vuković Sluzhebnik was printed in Venice, far outside Serbia, because of the suppression of Eastern Orthodoxy under the Turks (Ivic 1995). Massive repression of Church Slavonic also occurred under the Soviet Union. For nearly seventy years (1922-1991) the Communist state suppressed any form of religion in all of the Slavic states. As a result, Church Slavonic nearly disappeared, but with the fall of the Soviet Union Church Slavonic has experienced a resurgence (Bennet 2011, 3-6). The Eastern Orthodox Church, along with Church Slavonic, has reestablished itself as the spiritual center of life in many of the Slavic states, including Russia. In an interesting turn, Church Slavonic typefaces are now used on billboards, logos and advertising as a way to communicate a kind of traditional Russianness (Bennet 2011, 85-112).

Works Cited:

1. Bennett, Brian. 2011. Religion and Language in Post-Soviet Russia. New York: Routledge.

2. Ivic, Pavle and Mitar Pasikan. 1994. “Serbian Printing.” In The History of Serbian Culture. Translated by Randall A. Major. Middlesex, England: Porthill Publishers. (Accessed March 2, 2018) Reference link

3. Nesset, Tore. 2015. How Russian Came to Be the Way It Is. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers Indiana University.

4. OrthodoxWiki contributors, "Liturgical books," OrthodoxWiki, November 19th, 2012, (Accessed March 2, 2018). Reference link

5. Press, Ian. 2008. Topic on the History of Russian. Munich: Lincom Europa.

6. Wikipedia contributors, "Vuković printing house," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, last modified January 4th 2018. (Accessed March 2, 2018). Reference link

This spotlight exhibit by Alexandra Solodkaya as part of Dr. Johanna Drucker's "History of the Book and Literacy Technologies" seminar in Winter 2018 in the Information Studies Department at UCLA.

For documentation on this project, personnel, technical information, see Documentation. For contact email: drucker AT gseis.ucla.edu.