June 1865 issue cover page, with painstaking steel engraving.

Promotion of the U.S. Seven-Thirty Loan, index of "Embellishments," index of "Contributors and Contents."

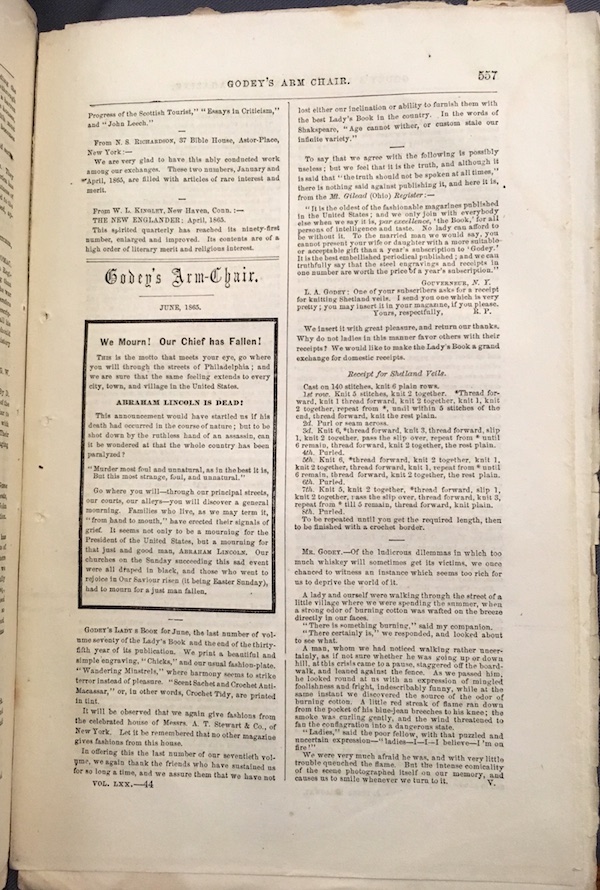

"Godey's Arm-Chair," featuring news of Lincoln's assassination; thanks from Godey; further praise for the magazine; "Receipt for Shetland Veils," which is to say, instructions to make them; and a humorous anecdote.

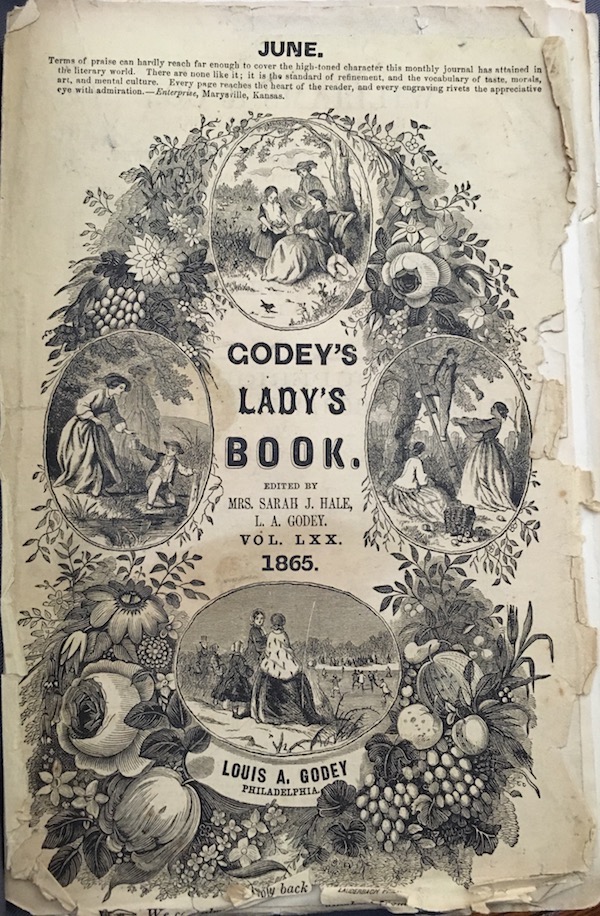

Godey's Lady's Book, June 1865

“Terms of praise can hardly reach far enough to cover the high-toned character this monthly journal has attained in the literary world. There are none like it; it is the standard of refinement, and the vocabulary of taste, morals, art, and mental culture. Every page reaches the heart of the reader, and every engraving rivets the appreciative eye with admiration.”

–Enterprise, Marysville, KansasSo reads the cover of the June 1865 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book, a Philadelphia-based women’s magazine that circulated nationally from 1830 to 1898. Louis A. Godey, founder and publisher of the periodical, was fond of printing the magazine’s praise (later in this issue: “It is a magazine of high moral worth,” says the Milan Radical), but the extra promotion wasn’t quite necessary. Godey’s Lady’s Book was the most influential women’s magazine of its time, with colossal distribution. At its acme in 1860, the magazine’s subscribers numbered 150,000, more than twenty times the average for U.S. magazines at mid-century. By this issue’s publication, less than a month after the end of the American Civil War, its subscriber count had dipped slightly but hovered at 100,000.

What did a women’s magazine look like in the nineteenth century? The June 1865 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book—its cover to your left—is 6.5” wide by 10” tall and bound loosely by deteriorating thread.

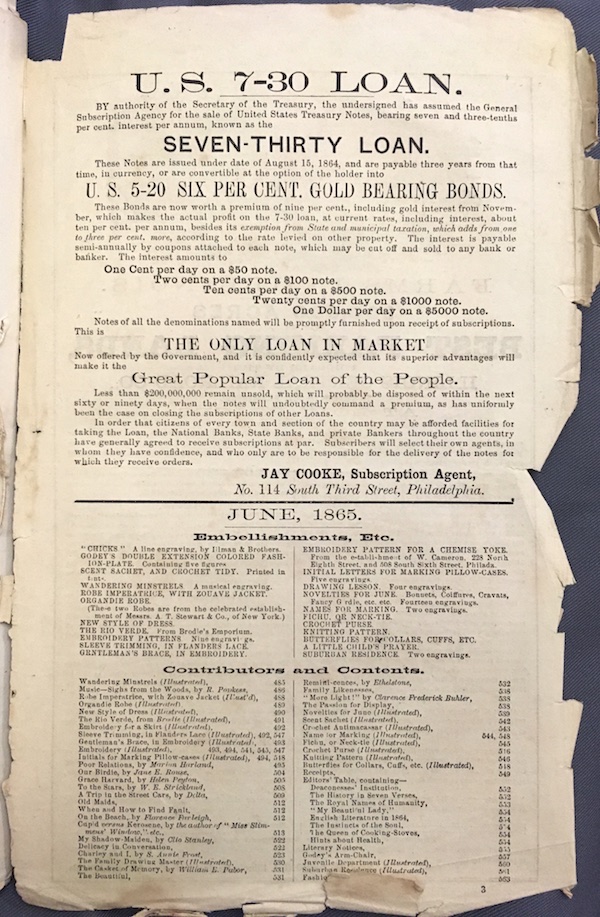

Most notably, it’s incomplete. Many pages of this issue are missing, including the “riveting” hand-tinted fashion plates for which Godey’s Lady’s Book was famous. The plates were so well loved that readers commonly removed them from the magazine for scrapbooking or to otherwise display; perhaps this tradition explains their absence here. The card-stock cover, above, nonetheless exemplifies the ornate steel engravings strewn through every issue. “Illustration mania,” as the Cosmopolitan Art Journal called it in 1857—this new trend for illustrated magazines and newspapers. Presenting our second image, which displays a list of June 1865’s engravings, or “embellishments.”

On the left side of this page, it’s possible to faintly see the perforations where the magazine was bound. On other pages of this issue, the thread looping them together still holds. Godey’s Lady’s Book was printed via multiple steam presses, and indeed the sweeping circulation of this monthly publication would not have been possible without this accelerative development in printing. Otherwise, its production was fairly manual: Besides coloring the plates, the large staff of mostly women also folded, sewed, and bound the magazine by hand.

Below “Embellishments,” we find the “Contributors and Contents” list, detailing the substance of the issue. Under Louis Godey’s helm, the Lady’s Book consisted of reprinted articles swiped from British women’s magazines, recipes, embroidery patterns, and the fashion plates. In 1837, Godey bought Boston’s Ladies’ Magazine and brought on its editor, Sarah Josepha Hale, as “editress” (her term) of the new, merged publication, re-titled as Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale kept the domestic tips, and begrudgingly, the fashion plates, but introduced poetry, short stories, and serialized novels, printed two columns per page. A quick skim of the author names proves many of them to be women’s. We can also assume that they were all American writers, and all of the work was original. These were the central tenets of Hale’s editorial strategy: as much writing by women as possible, only American writers, and only original work. In this last respect, her policy was antithetical to prevailing practice. Periodicals at this time routinely reprinted articles from other publications, without permission, acknowledgment, or further payment. In 1845, Godey’s Lady’s Book went further and began to copyright its contents—the first American magazine to do so.

Other notable sections of this issue include the “Editors’ Table,” a regular column written by Hale; “Godey’s Arm-Chair,” Louis Godey’s perennial platform; “Literary Notices,” a section for short book reviews; succinct notes of advice, like “When and Where to Find Fault”; and an illustration and architectural plan for a “Suburban Residence.” Advertisements, like the one above for the Seven-Thirty Loan, fill a few pages, but mostly promote innovative skirt design and other stylish temptations to an audience with cash to burn.

Despite this issue’s publication date, the advertisement for the Seven-Thirty Loan is one of the magazine’s rare references to the rather indelicate subject of the Civil War. Hale vaguely mentions “the sick and wounded of our Army and Navy” within a general discussion of Christian philanthropy in the “Editors’ Table.” And in “Godey’s Arm-Chair,” there is a small section announcing Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Our third image.

Lincoln died April 15, 1865; Godey’s Lady’s Book was no newspaper. But a national women’s magazine must be current to stay relevant! And print cannot help but to reflect the time it’s in.

Resources

Our Sister Editors: Sarah J. Hale and the Tradition of Nineteenth-Century American Women Editors by Patricia Okker: An exhaustive resource on Sarah J. Hale and Godey's Lady's Book, recounting, most usefully to me, the magazine's history, its support of authorial rights, and subscriber statistics.

Out in Public: Configurations of Women's Bodies in Nineteenth-Century America by Alison Piepmeier: In her chapter, "We Have Hardly Had Time to Mend Our Pen: Sarah Hale, Godey's Lady's Book, and the Body as Print," Piepmeier relays some information on the cover and binding used for the magazine.

A History of American Magazines, Volume II: 1850-1865 by Frank Luther Mott: Mott provides some of the historical backdrop of Godey's Lady's Book, remarking in particular on the popularity of illustrations in periodicals at the time.

"From the Periodical Archives: A Ramble Through the Mechanical Department of the 'Lady's Book'" by C.T. Hinckley: Hinckley offers a detailed account of the production of Godey's Lady's Book, emphasizing the hand-tinted fashion plates and use of steam presses.

"Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1874)" by Nicole Tonkovich Hoffman: Sarah J. Hale is thus illuminated as a patriotic, if polite, editress of the magazine.

This spotlight exhibit by Elizabeth Asher as part of Dr. Johanna Drucker's "History of the Book and Literacy Technologies" seminar in Winter 2018 in the Information Studies Department at UCLA.

For documentation on this project, personnel, technical information, see Documentation. For contact email: drucker AT gseis.ucla.edu.